Written by Rebecca Warwick

To label a film as a work by Quentin Tarantino, is to place it within a web of technique and references that have built up the coherent “Tarantino” style. Inglourious Basterds does have the typical grit and precision of a Tarantino creation, but through the lens of a historical action piece, the film boasts an alternative purpose.

The characters operate in a space where Second Word War locations, circumstances and figureheads collide with absurd violence and poetic revenge plots of the action genre. From the one hundred Nazi scalps that (aptly named) Lieutenant “Apache” Raine requests of the Basterds, to the gruesome fate that young Jewish-French Shoshanna intends to enact on the Third Reich, there is a hatred for the Nazi’s that is exhausted within every scene.

Within this liminal space of fact and fiction, Tarantino puts the Jewish characters in a position of capability, one which the historic reality he manipulates did not offer them. Shoshanna, after escaping the cruel fate of her family, embodies the anti-Semitic retribution fantasy, and carries out a perfectly executed plan which represents, to Tarantino at least, the desires of marginalised Jewish people in the war. However, while the film invites us to revel at the cruelty that the Basterds show every German soldier, to use the history of heinous acts to create a narrative where such violence is not eliminated, but reversed, poses a moral question on its viewers that Tarantino does not address. Is punishment for brutality, through brutality, any more commendable just because it is posed on the ‘enemy’?. It seems Tarantino sacrifices the question of the principles of revenge for the sake of his typical stylistic flair.

Tarantino subjects his viewers to an often uncomfortably slow movement of scenes towards an explosive conclusion, sometimes one which never materialises; but it is the potential of eruption that is powerful. Christoph Waltz’ SS superior Hans Landa is the personification of that potential, a character who communicates only through interrogation and an extravagance that unravels even the tightest of facades.

Without its copious references to classic cult cinema, from The Searchers to Scarface, Tarantino injects layers of cinephilia, and prioritises the importance of ‘the film’ and how it is weaponised. Using the understanding of the indispensability of the German cinema to the Nazi regime in the war, Tarantino weaves film into the “Allies” plots to undermine and overpower. Undercover British agent Lt. Archie Hicox is selected for his copious knowledge of German Cinema as a film critic, and his accomplice, double agent Bridget Von Hammersmark emulates a picture of the 1940’s German film star reminiscent of Marlene Dietrich. Tarantino also showcases the alternative power of cinema for violence. Hitler himself thinks it of valued importance that he attends the premiere of Goebbels’s “Nations Pride’, which leads to his death, as he is watching death unfold on screen.

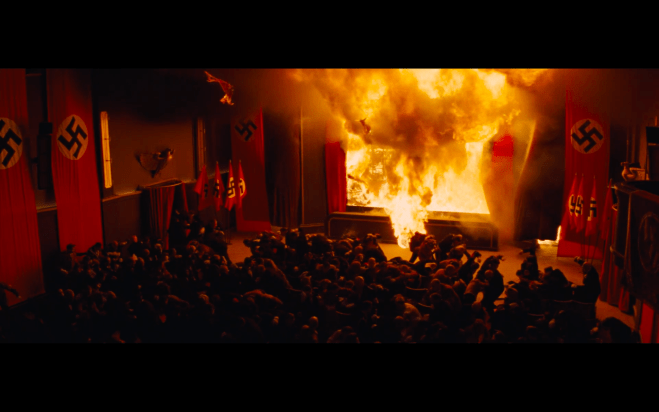

The tangible object of the film reel becomes the ultimate weapon that Shoshanna harnesses, forcing the Third Reich to watch helplessly as their own creation burns them to death in the cinema that is sacrificed for Tarantino’s ending of the war.

In Inglourious Basterds is Tarantino’s love letter to film; not only to the way it can alter history, but how indomitable it is to those that mobilize its influence.