Written by Jamie Pakes, Edited by Linh Duong

Last November marked the 10 year anniversary of Cartoon Network’s 2014 miniseries Over The Garden Wall. It featured only 10 short episodes running at approximately 12 minutes each, yet still managed to leave a lasting memory on both me and its avid cult following to this day. The show follows 2 brothers, Wirt and Greg, who with no apparent explanation have found themselves lost deep within woods known only as the ‘unknown’. To celebrate the 10 year anniversary, original creator Patrick McHale released a 3 minute stop motion short, a brief but welcome return to the unknown. In an interview with Inverse, McHale confessed that perhaps the series “should have been realised in stop motion all along” (McHale, paragraph 6). I found myself instinctively agreeing that the macabre and mysterious atmosphere of the series would have been perfect for stop motion, despite the actual animation having never seemed remotely inadequate. It was only after a few moments that I stopped to question what exactly it is that makes stop motion feel like such a natural fit. What is it that Over the Garden Wall and stop motion have in common? I pointed to the off-putting, unsettling effect that both tend to have, a slight creepiness that almost seems to escape proper definition, one impossible to fully put your finger on. The answer, I believe, lies in the relationship both share with the uncanny.

In researching the relationship between stop motion and the uncanny, I discovered a 2017 thesis by Dennis Crawte. One explanation provided as to why stop motion and the uncanny share such a strong relationship is the liminality between life and death. The uncanny is often created by a sense of liminality, with Crawte stating that “the uncanny occupies a liminal space at the threshold of perception” (Crawte, 2). Crawte goes on to argue that “Whilst its [stop motion] subjects’ appear imbued with the spark of the kinetic and a semblance of life, stop motion simultaneously embodies the spectre of inertia, lifelessness and death” (Crawte, 2). The ability to simulate the appearance of a living being is one of the key tenets of the uncanny outlined by Freud, and due to the medium’s constant stopping and starting, stop motion embodies and is uniquely equipped to portray a liminal space between life and death. Immediately, this jumped out as a possible explanation. After all, whether we realise it or not for most of the show, we eventually learn that Wirt and Greg’s trip to the unknown in OTGW is actually a strange kind of purgatory, one seemingly inspired by Dante’s Inferno, in which the boys traverse this exact liminality between life and death.

Episode 2 highlights this liminality as the brothers, alongside the talking bluebird Beatrice, encounter a strange and eerie village full of unknown figures wearing pumpkins over their heads. Throughout the episode the villagers carry with them a strange lifelessness; their bodies move just like anyone else, but their pumpkin faces are completely unmoving. This is particularly resonant with Crawte’s claims about stop motion, as these character’s movements possess the same uncanny duality of stop motion. Figure 1 depicts a specifically noticeable moment of this in which the villager turns their head accompanied by a creaking sound effect. By the end of the episode, it’s revealed that each of the villagers are actually skeletons dug up from a graveyard, with vegetables used to create a sort of disguise for them. Similar to the boys slowly moving towards their deaths, these villagers occupy a space between life and death that is inherently uncanny, exacerbated by the way in which their undead nature is initially hidden from the viewer.

Fig.1, episode 2

This liminality is definitely uncanny, however, it is only present in certain moments of the show. Whilst the boys’ purgatory does span the entire series, we are only made aware of it in episode 9, and it is only in retrospect that certain moments, such as the village leader’s claim that Wirt and Greg are ‘a little early’ to their undead village, can be linked to this theme. Furthermore, these villagers are only present for one episode, and are the only undead characters in the entire series. Therefore, whilst this purgatorial state does contribute to uncanny moments akin to stop motion, it cannot be attributed as the reason for the whole series’ uncanny quality.

Despite this, the liminality key to stop motion’s uncanny nature can still tell us a lot about OTGW. Kristiana Willsey mentions that OTGW faced criticism for its thin plots, which were often quickly and somewhat unsatisfyingly resolved. But Willsey describes this thinness as a “strategy” rather than a flaw, one which she links to the folk tales on which the show draws much inspiration (Willsey, 8). She gives an example from episode 5, when after a full episode of trying to gain a penny, Greg throws it away claiming, “I got no cents”. This grants a meaninglessness to the plot, and similar examples can be found in some other episodes’ all too easy resolutions. Episode 3 ends with an absurd reveal that a gorilla the characters have been fleeing from is a schoolteacher’s lover in disguise, and just like that the issue is resolved. In episode 6, the dreaded witch Adelaide who has been teased for several episodes as an important and dangerous character is quickly disposed of, melted accidentally by the night air.

These absurd conclusions arguably weaken the show on the surface, but they are also key to building its unique atmosphere. The stories are presented like bizarre fairy tales that do not always warrant a meaningful or sensible conclusion. Their endings are convenient and strange enough to draw attention to the fact that these are stories, preventing a full audience verisimilitude. McHale stops short of having the characters look down the barrel of the camera and speak to the audience, and yet he tampers with the 4th wall in a way that affects the viewer more subconsciously than a full breakage. The viewer is held in a strange, uncomfortable and uncanny tension within the 4th wall, unable to place their finger on what exactly is wrong, but knowing that something is. If the 4th wall was completely broken, then the audience could be relieved of this tension, as it would grant some clarity to what is happening and place them on more equal footing with the show, but this relief is never granted. This is the trait that lends OTGW such a compelling atmosphere that is so hard to replicate. These plots likely would not be enough to create it single-handedly, but there are other aspects of the show that I believe contribute to this wavering within the 4th wall.

One other factor is the extreme stylisation present in almost every scene. Chrisopher Lloyd’s vocal performance as the woodsman is delightfully over the top, pouring immense pain into every line even when it doesn’t seem warranted on paper. His main adversary, ‘The Beast’, is similarly overplayed by Samuel Ramey, although overplayed is not meant here as a criticism, as his voice is perfect for the ominous villain. Elijah Wood as Wirt and Collin Dean as Greg aren’t especially subtle, but when compared to these two are definitely less exaggerated. This may be due to their not belonging in the Unknown, but also serves to make the more exaggerated performances even more noticeable to the audience, giving them an unreal quality. Visually, every frame is dripping with artistic flare despite a relatively simple animation style. The backgrounds blend the styles of Gothic and Americana beautifully with often exaggerated lighting.

Fig. 2, Episode 2

The frame pictured above, taken from episode 2, forces viewers to take a small step back and appreciate its beauty, as the boys walk through the autumnal setting towards an all-consuming, heavenly light. The extreme audiovisual stylisation of the series is inescapable, and ensures that the audience is always acutely detached from what they’re watching, even without realising it. Again, this is very different from explicitly breaking the 4th wall, but has a Brechtian effect, subconsciously telling the viewer that what they are seeing is not entirely real.

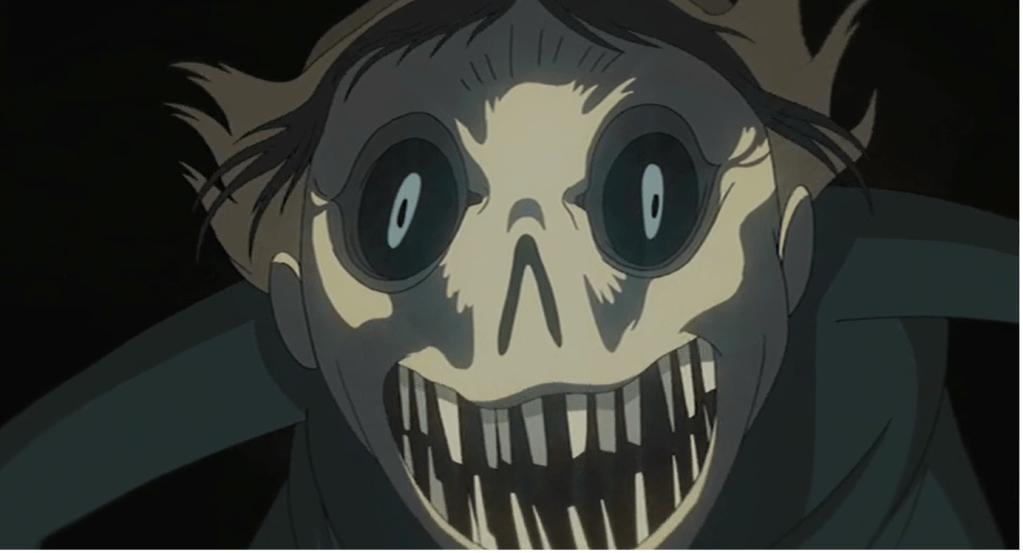

Another example of extreme stylisation that leads me into my final point can be seen whenever the characters face some sort of monster. With these monsters, the show often leans on horror traits, to an extent unexpected for a show initially airing on Cartoon Network. They remain concealed for most of the episode, but when revealed are often shockingly terrifying for a show aimed primarily at children. This is seen somewhat from episode 1, with a dog whose huge luminescent eyes and fatally sharp teeth bare down on the innocent Greg, its mouth stretching in a sickeningly unnatural manner all shown in close up. In episode 7 we have Lorna, who after appearing as a normal girl for most of the episode transforms into a horrifying ghostly creature. Her eyes become gaping pits holding thin blue irises, shadows cast down her face and uneven teeth jutting out from her ghastly grin as she is surrounded by enveloping darkness.

Fig. 3, episode 7

Rewatching as an adult, these moments admittedly were not as horror inducing as when I was a child, but they definitely surpass what most would expect from a children’s show. Even as a child, I remember being conscious that the show could only go so far in its horror elements, which creates a constant question in the viewer’s mind of how far it will be willing, or indeed allowed, to go. The constant presence of this question is the final and likely most important factor in placing OTGW in an uncanny relationship with the fourth wall. McHale does an effective job of gradually building the horror throughout the series. It begins with the dog in episode 1, and is followed next episode with the more subtle, folk horror creepiness of the pumpkin village. By episode 7 we have Lorna, and by the finale the viewer is made to wonder just how horrifying the antagonistic beast, which has been shown throughout as a silhouette, is going to be. This constant nagging feeling pushes beyond the diegetic world and into the real one. Like the general stylisation or absurd endings, it makes the viewer acutely aware of the construction of what they’re seeing, but perhaps not entirely sure why they feel this way. This element in particular gives the show a sort of rebellious quality, making the viewer urge it to push further and further against its generic constraints, but slightly worried what will happen if it does so.

None of the individual elements I have outlined here are enough make something uncanny. After all, lots of media contains absurdity and extreme stylisation without attaining this quality. However, I believe it is their combination that leads to the show’s aesthetic only typically found in works of stop motion. By refusing to ever take the final step of breaking the 4th wall, the tension created by being caught within it is never allowed to be relieved, there is none of the release that would come with the show explicitly telling you it is not real. This unusual relationship is what makes OTGW so unique, not quite like anything I have seen before or after, and what has made it stick in my mind for over 10 years.

Bibliography

Crawte, Derrin. “Darkness Visible: Contemporary Stop Motion Animation and the Uncanny.” Academia.edu, 2017.

McHale, Patrick. Interviewed by Kleinman, Jake. “Over the Garden Wall Probably Should Have Been ‘Stop-Motion All Along,’ Creator Says.” Inverse, 2023.

Willsey, Kristiana. “’All That Was Lost Is Revealed’: Motifs and Moral Ambiguity in Over the Garden Wall.” Humanities, Vol 6, Iss 3, 2016, pp. 51-61.