Written by Dylan Day

Trainspotting is as whimsical as it is putrid. Adapted from the critically acclaimed book in which it shares a name, it too shares the novel’s dedication to its setting, time and place. The film is ever fascinated with the culture of the 90s and its youth. The conversations characters share with each other, seemingly pointless talk of popstars, sex and football create a level of relatability to coincide with a good helping of gunge and nihilism synonymous with the attitudes of art in the 90s. With a mixture of 70s rock and roll and the at the time contemporary dance, electronica and house prevalent in clubs across the country, the film pulls you along through its somewhat disjointed plot through the sheer momentum of its style. It knows when to keep the pace up, when to draw you into the trance. It becomes intoxicating in that way, paradoxical in how it manages to be so pleasurable despite its bleak topic but more importantly it knows when to rip it away.

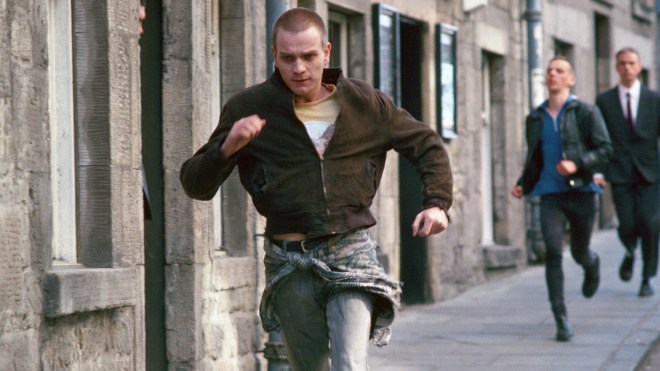

It separates the states of mind through its set production, the drug dens swallowed by its deep, dark, reds and greens contrasted by the mundane greys of the outside world. It takes a holistic view at drug addiction, as Renton (Ewan McGregor) puts it himself in the opening montage: “People think it’s all about misery and desperation and death … but what they forget is the pleasure of it.” It seeks less so to examine the nature of the addiction itself, or the many reasons someone may become an addict, but rather the bodily experience of being an addict, the people you associate with, the day-to-day desperation and dependence and the horror and pain that comes with Renton’s seemingly pointless attempts to get clean. It uses the camera as a vehicle in which to take us through the emotional roller coaster of heroin, purposely making you uncomfortable through how close and disorienting the camera placement may be.

The paradox is an enthralling fight within the film, so much so that it is often confusing to viewers whether its theming and message is ultimately anti-drug or not. Renton questions the morality of heroin and what society deems to be acceptable drug use. Begbie (Robert Carlyle), the only non-user of the group is often seen in a worse light than those who partake through his indiscriminate violence towards those around him and yet within their social circle is deemed as a positive influence. The nature of Renton’s depiction particularly through his voiceover paints him not as a mindless addict despite his own assertions that he is “stupid”. He instead comes across as extremely perceptive and often philosophical both in his relationship with drugs but also the nature of the world he lives in. He displays no real reason for his addiction, he has no tragic backstory and outright refutes the idea that he is in any way a good person and yet I feel it is for these exact reasons that he becomes so much more relatable to the audience, almost to the point of being sympathetic. Ultimately the film is though his eyes, delusions and all. We see and feel his pain, his joy and his struggle, culminating in a very real, dark and enthralling view of life as a heroin addict.