Written by Patrick Maslin, Edited by Abigail Aldrich

Batman & Robin is a film often viewed from the perspective that it is ‘so bad it’s good’. This is the idea of enjoyment proceeding directly from the failures of the director, writer, and other members of the production team to communicate their intent, ultimately conveying something completely different. Strohl claims that defining an artwork as “so bad its good means that an artwork is bad in the final sense but that one still enjoys watching it, not because one judges it aesthetically valuable, but because one enjoys making fun” (2022). This essay will attempt to disrupt the limiting idea that Batman & Robin is only valuable because it is a bad artwork. To be clear, the intention of this essay is not to declare Batman & Robin a perfect film or even refute any of the criticisms levelled against it. The intent is simply, given the benefit of time, to first analyse its often-ignored contributions to Batman’s mythos and properly situate it amongst other Batman stories, and secondly to hopefully find the value in viewing Batman & Robin as a typical so good it’s good film.

Firstly, as it is often necessary to do with media that are viewed from this ‘so bad it’s good’ mentality, this essay will acknowledge the film’s faults and why it was despised at the time of its release. It has been observed numerous times over the years that Batman & Robin has some very sexist depictions of its female characters with Poison Ivy being the most archetypal villainised fem seductress. These simplistic stereotypes also extend to the setting with the presentation of South America and even more so with the emulation of that aesthetic at the rainforest fundraiser. Another element key to framing the hatred of this film is to take into consideration the dominant understandings of superhero films at the time. Even more so than today the superhero genre was seen as “people resorting to fantasy” (Toomer, 2019), “with nothing authentic at its core.” (Dequina, 1997). It most certainly can be argued that Batman & Robin “just reinforces the most widely held stereotype about comics–that they’re just for kids.” (Dequina, 1997). Therefore, I imagine, without some of the depictions of Batman we have had over the last two decades, I too would find it difficult to watch a movie where one of the most nuanced protagonists in all of comics is reduced to a simplistic stereotype of himself.

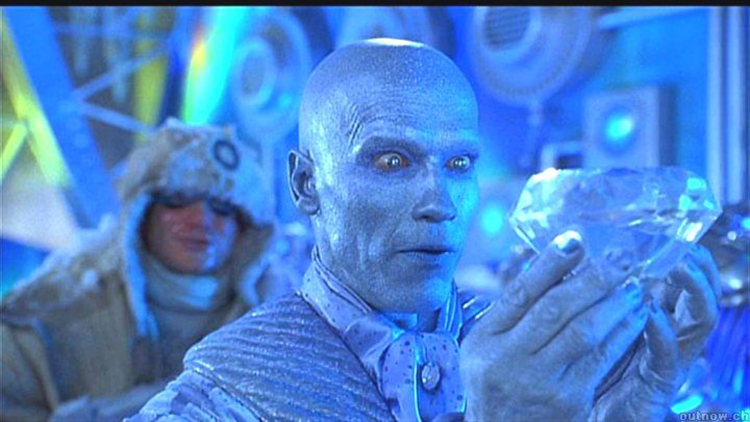

There are of course other flaws, such as the representation of Bane, however, these criticisms are by far the ones that are most consistently brought up in discussions of the film. Since they have been understood, it is possible to discuss the elements of this movie that stand the test of time. Firstly, and whilst this may not be representative of anything great within itself, it is still worthy to note that there is very obviously a great deal of care for Batman and his surrounding mythos within this film. Batman & Robin uses Batman The Animated Series’ (henceforth Batman TAS) version of Mr. Freeze and even incorporates elements that creator Paul Dini expressed regret over not using. This element of the film is seen for example in the supervillain’s tears freezing as he contemplates his failure to save his wife. Batman TAS producer Bruce Timm recounts how “”when Paul was working on the actual script, he had a sudden flash of his own: the image of Freeze in his cell… His tears turning to icy snowflakes, an image which never appears in the finished cartoon, strangely enough! This gave him the springboard for Freeze’s motivation.” (Harvey, no date). This clearly demonstrates a respect for previous incarnations of Batman and a wish to complete the visions of other artists who have worked on Batman. This demonstrates not only Schumacher’s desire to accurately portray elements from one of the most revered Batman adaptions of all time, but also that there is very clearly an intent within this movie to build off and reinterpret what it is adapting. Whether Schumacher’s use of these elements was successful is an entirely different and far more subjective matter. However, the point remains that Schumacher worked with the intent to build off the work of others to create something as emotionally complex as what came before.

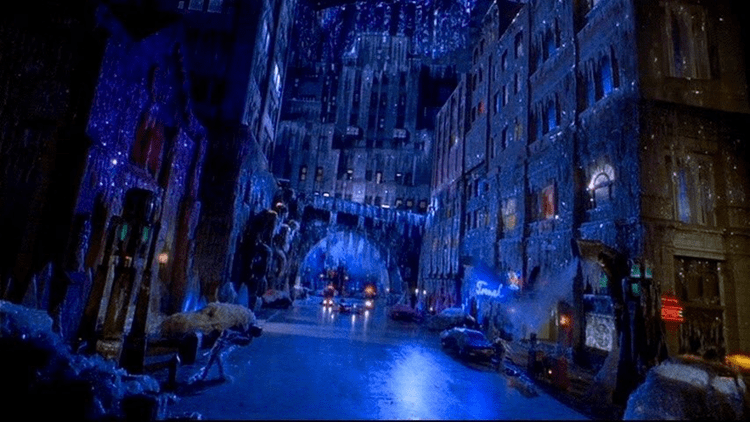

The film even pushes some of the ideas within the previous Batman films further, for instance, the structure of the city. Many have said that the look of Gotham City (made by the legendary Anton Furst) is one of the defining features that makes Tim Burton’s Batman so incredible. As Burton himself states “It has an operatic feel, and an almost timeless quality (Burton, 2008: 77). However, in my opinion, Batman & Robin contains my favourite live-action aesthetic for Gotham City. It is overdesigned, overcrowded, monstrous, and bizarre in a wonderfully fantastical way. The combination of giant overbearing spires, endlessly crisscrossing bridges, and overwhelmingly bright lower streets convey an over-industrialised nightmare that gives Gotham City this oppressive presence which makes Batman all the more inspiring for his ability to both figuratively and literally rise above this horrible city. It is beautiful, purely visual storytelling.

Another piece of Batman media that Batman & Robin draws influence from is the 60s Batman TV show (henceforth Batman 66). For example: Batman using a surfboard, Mr Freeze being a thief rather than a man seeking vengeance against those that have done him wrong, the sheer amount of highly specific gadgets, the number of puns, and the themed henchmen are all elements present within the 60s show. Whilst Batman 66 was initially designed to be a parody of the Silver Age comics, leading some to argue there is no room within modern Batman to accommodate his campier incarnations, this is disproven by some of the comics that this essay will later use to discuss the recurring appearances of camp elements within Batman stories. For instance, the immensely popular Batman: Wayne Family Adventures frequently has the characters fight ridiculous villains such as the Condiment King. It is also disproven by the fact that the 60s version of Batman has returned time and time again (often in animation like Batman vs Two Face). So given that the audience for Batman 66 persists, it is clear that there is room to accommodate a Batman who is not constantly preoccupied with his psychological turmoil. Therefore, it stands to reason that this film’s exploration of the humorous elements of Batman’s world are no less valid than any of the darker investigation that we have recently experienced.

Another criticism that has been made against this film is that its attempts to mix campier depictions of Batman with more psychologically nuanced takes like Batman TAS make the film come across as disjointed. However, two decades later another film would attempt this combination of tragic and comedic with a great success: The Lego Batman Movie. This demonstrates that this mix of camp and emotional turmoil is not an inherently bad idea. Furthermore, many of these homages push the original jokes of the 60s series further with the budget and special effects at Schumacher’s disposal. For instance, as fun as it is to see Batman enter a surfing competition against the Joker, it cannot quite compare to seeing Batman and Robin surfing an explosion back into Gotham City in an attempt to capture Mr Freeze. This showcases how this film reinterprets old elements of Batman’s mythos to fit the story it is telling, once again highlighting the elements of a good adaption that this movie possesses.

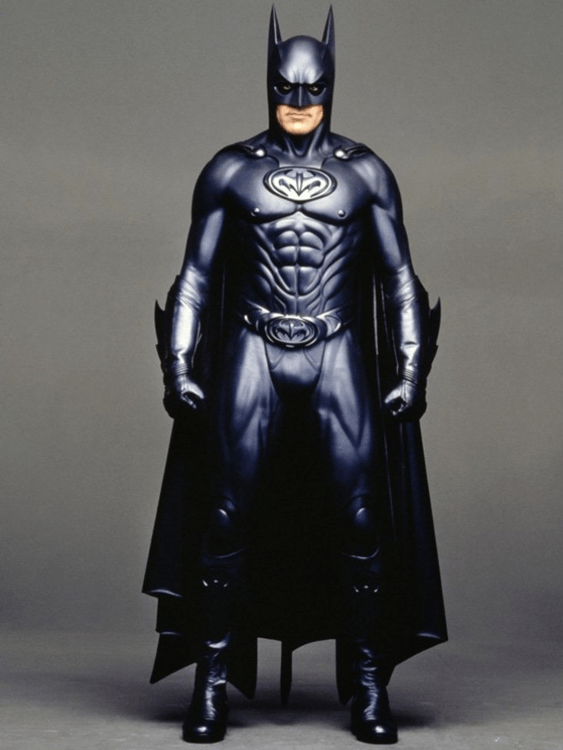

Even the music of this film has a lasting impact, with the Legendary Hanz Zimmer (who himself scored Nolan’s Batman trilogy and Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice) referring to the score by Elliot Goldenthal as “the most glorious statement of Batman I’d ever heard.” (Ankers-Range, 2021). The score wonderfully builds on the melancholic work of Danny Elfman to create a more hopeful Batman theme that comes across as a hero’s triumph. In the overture alone you can hear this transition from Elfman’s well-known theme to something vibrant, with the inclusion of the piano adding a sense of wonder that undercuts the music’s sombre tone. This demonstrates that in spite of its original perception, this film builds off what came before and reveals that since this Batman (George Clooney) now has Dick Grayson (Chris O’Donnell) in his life, he is allowing himself to once more be hopeful that what he is doing is the right thing. This is an evolution from Burton’s films where he felt compelled to do things even if he did not know why: “Sometimes I don’t know what to think about this. It’s just something I have to do.” This in turn reveals that Batman has come closer to achieving of goal of bringing order and peace to Gotham. This highlights Schumacher’s desire to develop and evolve the story of Batman, as it would have been far easier to resort to Burton’s already existing vision of Batman and his impact upon the world.

It is possible to brush off some of these elements as simply parallel thought, but Schumacher’s love for the character, and the sheer amount of these references and elements from other pieces of Batman media, display a clear dedication to present a Batman that is true to many other versions of the character. It even shows that the reinterpretations of this film have not been forgotten or brushed under the rug but instead have been built upon by other creators, which has led to creative projects that have gained artistic and popular acclaim. Moreover, this is one of only two Batman films where none of Batman’s actions or inactions directly result in a death of an individual, which clearly shows a commitment to preserve Batman’s ‘No killing Rule’, which a number of other adaptions, most notably Zack Snyder’s Batman vs Superman, lack.

Now we can better understand how the influences of previous Batman works have been situated within the film, as well as understanding its own influence upon Batman’s mythos and later Batman works. While elements from a film that become recurring in the mythos they adapt should not inherently be celebrated, it is key to note the presentation of the examples that this essay is going to discuss. These are not mocking jabs at how ridiculous the ideas within this film are, in the vein of Spider-Man: Into The Spider-verse mocking Toby Maguire’s dancing in Spider-Man 3. These are ideas that have been used as elements within critically acclaimed dramatic psychological explorations of why Batman exists and what he views his purpose to be. This is not to say these parodies do not exist, for instance, in The New Batman Adventures episode 19 “Legends of the Dark Knight”, a character named Joel hanging outside a shoemaker store says that he loves Batman because he wears “tight rubber armour” and has a car that can “drive up walls”, only to be mocked by his friends. However, these representations are far outnumbered by the film’s other influences and reinterpretations.

A key figure to look at when discussing the Batman Mythos is Poison Ivy (Uma Thurman). Poison Ivy being linked to chemical weapons, while not created by this movie, has played a part in popularising that interpretation. There are few variations of Poison Ivy that so closely connect her to chemical weaponry as this depiction, nor any that focus on her body as something fundamentally toxic. This can not only be seen through Jason Woodrue (John Glover) attempting to sell Ivy’s creations as weapons to the highest bidder but also the description Pamela gives of her own body “and filled my lips with venom.” Additionally, this description emphasises that this toxicity is not something Ivy controls, which is another element many other interpretations lack; for instance, BTAS or the Harley Quinn tv show. This focus on chemical weaponry and inherent bodily toxicity has no doubt inspired the celebrated depiction seen within Batman Unburied, which fully explores an attempt to turn a human being into a living weapon, and the psychological impact that has on an individual. This does reveal how even in the worst, most sexist, aspects of this film, there persists promising ideas and intentions that have paved the way to celebrated depictions of this character.

The impact of Batman & Robin extends into comics where the climactic scene of this film, focusing on a gigantic freeze gun situated at an observatory, was used for the ending of Sean Murphy’s critically beloved Batman White Knight. Murphy takes a number of elements from many different understandings of Batman, from the name of the Joker being Jack Napier (something created within the Burton movies), to Batgirl using the tumbler from Nolan’s Batman trilogy. However, most prominent within the story are the inspirations Murphy takes from Batman & Robin, for instance, the climax of the comic revolving around a giant freeze gun (whose design is directly taken from Batman & Robin). This demonstrates how iconic the aesthetics of Batman & Robin are, and that they reside comfortably within the Batman mythos to the point where they can be reinterpreted by a completely different artist and maintain their appeal. This is not the only element that Murphy reinterpreted from Batman & Robin. Within White Knight Alfred is dying and Fries’ technology is used to keep him alive. This reveals the potential present in the ideas and themes of Batman & Robin; comparing Mr Freeze’s love for his wife Nora to Bruce’s love for Alfred helps reflect the effects of grief, and the need each character possesses to stand against death. In fact, comparing White Knight against Batman & Robin highlighted to me the techniques Schumacher uses to show Batman becoming similar to Mr Freeze (Arnold Schwarzenegger). Both characters are displayed detaching themselves from potential romantic connections and both show contempt for those working alongside them. Moreover, the conflict between them is resolved not solely by action, but by Batman playing to Freeze’s heart and asking him to remember his calling as a doctor to save lives leading him to hand over a cure for Alfred’s (Michael Gough) condition. Whilst I do not find it quite as poignant as in White Knight, the comparisons reside in both texts, and Schumacher does use it to effectively highlight the effects of grief and isolation. Is it diminished by the comedic elements? Partially, but I do not believe they completely ruin this thematic component. If that was not evidence enough that the elements of Batman & Robin have been reinterpreted in effective ways, Murphy goes one step further and even incorporates the numerous freeze puns that Schumacher made within the film to full effect when Freeze takes a stand against the villain of the book, Neo Joker, stating “I’m sorry but I’m all out of ice puns.” This evidence reveals that the ideas and emotional themes of Batman & Robin firstly contribute to other more critically acclaimed depictions of the character, and secondly, display how grief and fear of loss can drive even the best amongst us to resemble the worst.

Even the speeches within the film bear eerie similarities to their counterparts in more recent comic books. For instance, within Batman, The Joker War, Alfred delivers a speech about Batman standing against chaos and therefore death. “But he is Batman, and he needs to accept the world that he lives in. Accept what he can control. And in doing so he can save the lives of so many people within the city that he loves. Every life he saves is a stand against death.” This very clearly bears similarities to the speech Alfred gives to Bruce in the film: “For what is Batman? If not an effort to master the chaos that sweeps our world. An attempt to control death itself.” It is difficult to determine whether this film inspired Tynion, but the similarities do present a collective understanding of the character. This reveals that this film possesses not only an understanding of Batman (which cannot be said for all adaptations), but an attempt to portray the similarities between Batman and Mr Freeze with them both attempting to stand against the unstoppable death for the sake of those they love. Furthermore, it showcases that other writers have built on the work of Schumacher to great success, which shows how valuable his contributions to the mythos of Batman are.

One final element of the film that deserves to be discussed is the gay gaze. Batman from a gay perspective has been analysed by infinitely more intelligent people than I. If you prefer a much better discussion of this specific element this essay happily recommends The Many Lives of the Batman, specifically Andy Medhurst’s essay “Batman, Deviance and Camp”. I will say that despite the film’s obvious sexualisation of female bodies (Poison Ivy, Mr Freeze’s nameless henchwoman and Batgirl) that play into an objectifying male gaze, there is a lot of usage of male bodies as something to be viewed sexually. It is important to note that this film was created before the surge of shirtless scenes within the superhero genre, so at the time seeing these costumes that not only enhanced but drew attention to an actor’s musculature and most commonly attractive features was groundbreaking. This eroticism is enhanced by the body parts Schumacher chooses to focus upon, namely the famous or perhaps infamous butt shots as the caped crusaders suit up to fight crime. This further demonstrates a willingness to view these (admittedly fake bodies) as not only something to admire but as a sexual prospect.

In this way, it could be argued that Schumacher predicted current superhero tropes given how often modern-day live-action superheroes are viewed in this capacity. Moreover, through the constructed nature of these bodies, the film could be remarking on how overly crafted the appeal of these muscular bodies is. Another way Schumacher uses this construction of musculature is by incorporating it into the architecture of this world with numerous giant masculine bodies either being used to support structures like the observatory or simply being built into the landscape of Gotham. From this, it is possible to see how Schumacher is using the gay gaze to convey environmentally the weight of Bruce Wayne’s responsibility. After all, who holds up Gotham City more than Batman? By visualising the weight of Batman’s responsibility Schumacher enhances the suffering Bruce experiences, and through its destruction reveals the impossibility of Batman’s task. Even Bruce cannot support and defend Gotham alone.

Another element to contrast against this gay gaze to show its impact is the representation of heterosexuality within Batman & Robin, more specifically the ways in which Bruce interacts with potential love interests. For example, the use of Poison Ivy as a villainous seductress to drive a wedge between two male friends could be viewed as an attempt to shut down a gay relationship. Whilst that argument could be considered a stretch, it is supported by other elements within this movie especially the representation between Bruce Wayne and his other potential love interest Julie Madison (Elle Macpherson). They continually show little to no emotional connection and when she seeks his commitment to a more long-term relationship, he refuses her and shows complete disinterest in her, something that is never resolved by the end of the film. Furthermore, the scene of Bruce rejecting Julie’s desire to get married is aggressively easy to read as him referring to a different sexual orientation rather than being Batman with lines such as “I’m not the marrying kind” and “there are things about me that you wouldn’t understand”. Although it is Ivy’s intrusion into the scene that is affecting his romantic life, it is fairly easy to read that intrusion as Bruce facing the overwhelming pressures of heterosexuality that exist both in his public and private life. Therefore, by having Ivy appear in this, Schumacher is showing how pervasive these pressures are. All these factors create a gaze clearly designed to appeal to gay audiences (especially given how much theory is written on this film through that lens), and in doing so Schumacher further opens the superhero genre to queer audiences, all whilst critiquing the glorification of male presenting bodies.

From this analysis, I believe it is possible to see the numerous positive elements of this movie and how they have lived on in various other pieces of media. It is also important not to ignore this film’s negative effects. It did, for example, make producers reluctant to adapt Batman into live action for several years, a reluctance that led to Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, which is one of, if not the most, celebrated depictions of Batman of all time. This essay has hopefully demonstrated the longstanding and beloved contributions Batman & Robin has made to the Dark Knight’s unending crusade. Perhaps, to see the value in this film, all that is required is a slight shift in perspective to accommodate a Batman that, whilst more camp, is nonetheless still a worthy exploration of the hero.

Bibliography

Ankers-Range, Adele. “Hans Zimmer’s Favorite Batman Score Is Not the One You’d Expect.” IGN, IGN, 14 Oct. 2021, http://www.ign.com/articles/hans-zimmer-favorite-batman-score-not-one-you-expect.

Burton, Tim, and Mark Salisbury. Burton on Burton. Faber & Faber, 2008.

Dequina, Micheal. “Archive Volume 20.” The Movie Report Archive, Volume 20 – TheMovieReport.Com, themoviereport.com/movierpt20.html#b&r. June 1997, Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Ebert, Roger. “Batman and Robin Movie Review (1997): Roger Ebert.” Movie Review (1997) | Roger Ebert, http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/batman-and-robin-1997. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Harvey, Jim. The World’s Finest – Heart of Ice: A Look Back, dcanimated.com/WF/heartofice/interview/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Medhurst, Andy, “Batman, Deviance and Camp”, in Pearson, Roberta E., and William Uricchio (editors), The Many Lives of Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. BFI, 1991: 149-163.

Murphy, Sean, et al. Batman, White Knight. DC Black Label, 2020.

Strohl, Matthew S. Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

Toomer, Jessica. “‘the Boys’ Comic Creator Garth Ennis on Why He Hates Superheroes.” UPROXX, UPROXX, 24 July 2019, uproxx.com/hitfix/the-boys-amazon-garth-ennis-interview/.

Tynion, James. Batman the Joker War, DC COMICS, S.l., 2021.

Filmography

Batman (Tim Burton, Warner Bros, 1989, US)

Batman & Robin (Joel Schumacher, Warner Bros, 1997, US)

Batman The Animated Series (Bruce W. Timm, Eric Radomowski, Warner Bros. Animation, 1992-1995, US)

Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice (Zack Snyder, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2016, US)

Batman Vs. Two Face (Rick Morales, Warner Bros. Animation, 2017, US)

Harley Quin (Justin Halpern, Patrick Schumacker, Dean Lorey, Warner Bros. Animation, 2019-,US)

The Lego Batman Movie (Chris McKay, Warner Animation Group, 2017, US)

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, Rodney Rothman, Sony Pictures Animation, 2018, US)

Spider-Man 3 (Sam Raimi, Columbia Pictures, 2007, US)

https://sequel.transistor.fm/episodes/batman-and-robin

LikeLike